By ESG Analyst Lars Tum

Introduction

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) values play a vital role in today’s financial investments and political decisions. But increasingly, these aspects also are applied in major infrastructure projects. However, ESG aspects were already implied in infrastructure planning before it even existed as today’s definition of ESG.

By transitioning from industrial to post-industrial, many urban areas faced the challenge and took the chance of becoming more enjoyable, inclusive, and sustainable.

But why does this matter? And what makes infrastructure changing from being useful to also being enjoyable possible?

Infrastructure – a problem, or an opportunity?

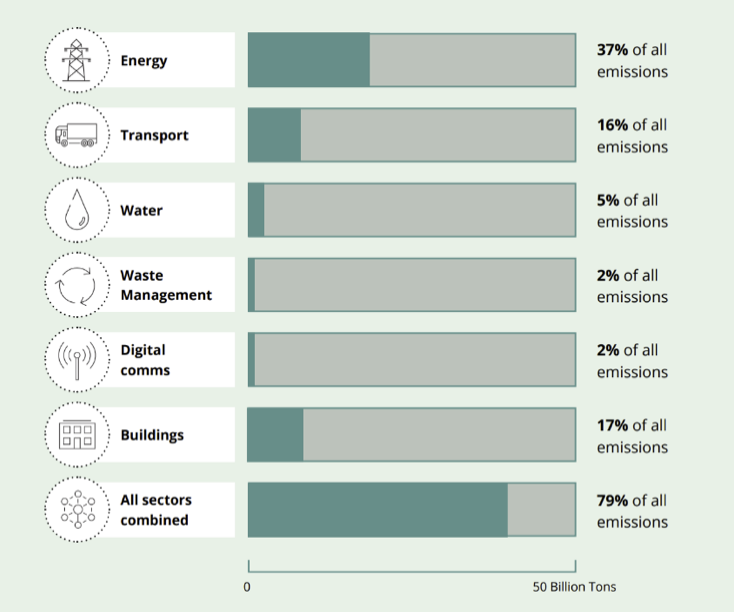

Scarce resources, high consumption rates, and high anthropogenic emissions led various decision-makers to establish or work towards sustainable principles like a circular economy or Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, infrastructure is a major polluter in worldwide emissions. A report from 2021 by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) shows that 79% percent of all greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to infrastructure (figure 1). Moreover, 88% of adaptation costs are connected to infrastructure.

This can be regarded as more of a problem – or as “[…] a unique chance for governments to accelerate sustainable development and climate action” (UNOPS, 2021, p. 18). Not only is this opportunity ecological; but it is to a high degree also economically profitable. Over 20 years, every US$ invested in infrastructure can fuel the economy with an additional 3.7 US$ (KPMG, 2020).

Policymakers can therefore shape the ecological and economic future drastically by making decisions regarding infrastructure funding and investments. To make this an attractive business model, governments need to give investors low barriers to realizing ESG-related projects.

Innovation.

In the past 15 years, technological innovations made sustainable alternatives possible and economically reasonable, eventually to a degree where it nowadays can be regarded as competitive. Sustainable energy production has become cheaper than the cost of fossil fuels(International Renewable Energy Agency, 2021, p. 55). This is due to cheaper technology production costs and policies, which lower costs or even support sustainable alternatives. But policies have to keep up with innovation so as to not miss the opportunity for sustainable change on a big scale.

Figure 2: London Array Windpark, UK

Although technological innovations matter in the field of sustainable energy production, infrastructure planning has already implemented many ESG values in past innovative projects. Since industrialization was mainly driven by the expansion of transportation, automatization, and infrastructure (Landes, 2014, p. 4), many industrial sites in major urban areas had to be either demolished or severely modernized.

A famous example of a successful ESG-related project is the Highline in New York City, USA. This former food delivery railroad from the 19th century was abandoned and was about to be demolished since it was first too dangerous and afterward impractical due to the rise in trucking. Finally, in 2003, an “ideas competition” led to preserving the railroad and turning it into an urban landscape.

The High Line, a 1.45-mile-long greenway, today represents one of the most famous post-industrial projects turning a former industrial site into a green, public space (Friends of the High Line, n.d.).

Summary

A globalized world with vast connected urban areas can’t exist without a functioning infrastructure. And this comes with a high monetary cost. We need to make sure that this massive substructure of society utilizes as many ESG opportunities as possible whilst not lacking functionality, as it has such leverage on the global economy and emission levels. It is up to policymakers and governments that infrastructure can be reliable, functional, and sustainable at once. But with innovation, there comes opportunity.

References

Friends of the High Line. High Line: History. https://www.thehighline.org/

International Renewable Energy Agency (2021). Renewable power generation costs in 2021.

Landes, D. S. (2014). Introduction. In D. S. Landes (Ed.), The Unbound Prometheus (pp. 1–40). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819957.003

Threlfall, R. (2020). The sustainable infrastructure opportunity: The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the need to strengthen our resilience to future threats to humanity – including climate change. https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2020/06/covid-19-recovery.html

UNOPS (2021). Infrastructure for climate action, 1–39.