By ESG McGill Analyst Lori-Ann Bernard

Energy remains the central point of discussion within the environmental movement. Fossil fuels remain the energy source that states depend on the most. With energy alternatives identified, research has labelled some solutions ‘clean’ while others are ‘transitional.’ Transitional energy sources are alternatives to fossil fuels that are less polluting; however, they are not carbon neutral and still produce some emissions. Identifying options that result in pollutants has led to questioning whether these sources should be considered climate solutions. As clean energy is the goal, should we consider transitional solutions? Are transitional energy sources worth current investment, or should resources be dedicated to clean energy sources only?

An example of a transitional energy solution is Waste-to-Energy (WtE); This energy source comes from converting municipal solid waste (MSW) into energy, most often through incineration. In the book Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming by American environmentalist Paul Hawken, WtE is named a ‘regrets solution’–an alternative that, although greener than current energy sources, is not ‘clean’ and is tied to much controversy. As we walk through the WtE debate throughout this article, the question remains: do transitional solutions stifle the work toward other long-term environmental objectives?

As previously mentioned, WtE produces heat and electricity from burning municipal waste from both households and commercial production. MSW refers to burning waste that would otherwise end up in landfills. Landfills are known for their significant methane emissions and the leaching of toxic chemicals into groundwater. In the US, landfills are the third largest source of methane emissions (YaleEnvironment360). In addition to the health effects landfills have on nearby communities–which also contain many equity issues–they take up a lot of space and are costly. The laundry list of landfill-related problems has pushed many European countries to institute landfill bans (YaleEnvironment360). As a result, WtE has emerged as a viable alternative to landfills.

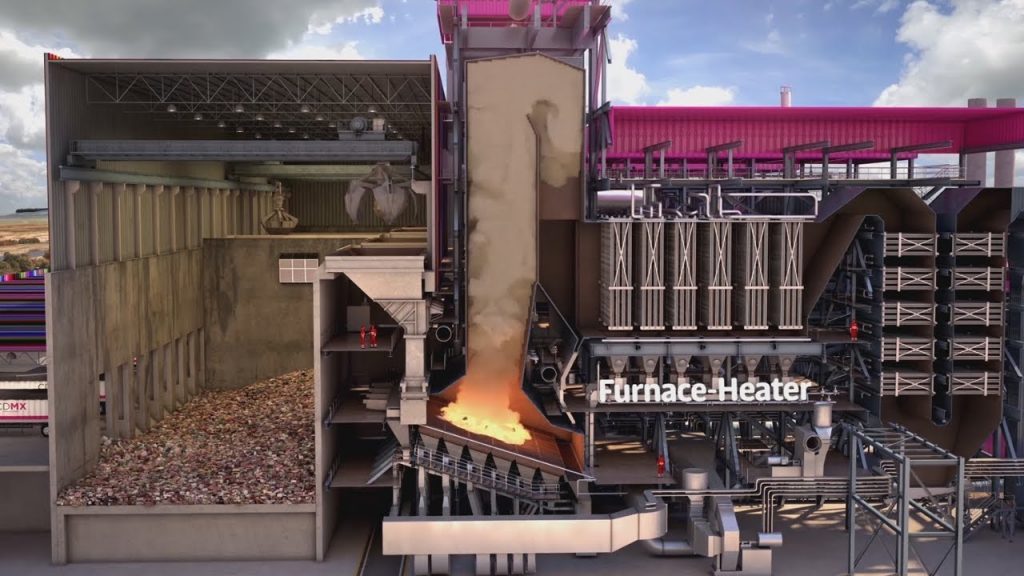

For WtE energy, burning waste produces heat and steam to drive a turbine, creating energy that municipalities can use for heating and electricity. While this can be considered one way to ‘reuse’ waste, there are by-products within the process that make this method of energy production not clean. A toxic ‘fly-ash’ results from burning waste released into the air and can contaminate nearby water sources, affecting local communities. Though the intensity of pollution may be less than fossil fuels, WtE is by no means carbon neutral.

Despite the pollution, WtE is considered a sustainable alternative, especially in comparison to landfills. WtE has become popular in island states, such as Japan, where space for landfills is limited, and Europe, where landfill bans have gradually increased (Drawdown). However, particularly in Europe, despite subsidies and policy support for constructing WtE plants, proponents have received a lot of pushback from environmental organizations such as Zero Waste Europe. Advocates of zero waste argue that WtE, while producing less methane than landfills, harms zero waste efforts by encouraging waste production. Contracts for WtE plants, dealt with by local municipalities, confirm a waste stream for the next 20-30 years for the functioning of the plant and the production of energy (YaleEnvironment360). Zero-wasters strive to recycle all waste (through recycling and composting); therefore, many believe these plants stifle progress to decrease waste and instead promote waste creation.

Additionally, burning waste for energy, they argue, removes the ability to reuse materials. The materials used in production are lost forever. However, to this argument, proponents of WtE argue that despite waste production decreasing, there will always be residual waste: is true zero-waste even attainable? Also, some view the burning of waste as a way to transfer the energy used in production to the energy households can reuse through heating and electricity. There is also the belief that shipping waste from other regions and states is possible and would keep WtE profitable (YaleEnvironment360).

Further, opponents of WtE argue that investment into these plants would be wasteful as the European Commission’s New Circular Economy Plan (CEAP) threatens the future of the WtE sector. With the CEAP aiming to halve residual waste by 2030, it calls for the commission to define a new approach to waste management of non-recyclable MSW (Clean Energy Wire). WtE could threaten the development of a circular economy if waste is needed to feed energy production at these plants. With this, many critics view WtE as a temporary solution that requires gradual phasing-out in the coming years. Therefore, the focus and investment in climate solutions should be on clean energy solutions. Proponents, however, maintain that WtE is a way to address current waste and landfill issues. Despite its polluting qualities, it remains less polluting than current primary energy sources and would aid the energy transition. They also address the production of by-products by citing their possible use in construction with making asphalt and cement. While there are other emissions related to the production of these materials, is it logical to assume that, with current levels of development, there will not be a market for these materials? (Clean Energy Wire).

According to Clean Wire Energy, energy from waste accounted for 2.4% of Europe’s total energy supply in 2018. Subsidies for WtE plants have decreased in recent years as consensus around the finite nature of the industry has become the center of the WtE debate. The question remains for many, are investments into transitional solutions, such as WtE, beneficial? The complex contexts surrounding this energy source solution have pulled many countries, principally Europe, in many directions relating to its benefits and consequences. As landfills and overconsumption are two significant problems within the environmental crisis, many view WtE as a viable solution. However, is WtE merely a temporary, short-term solution that will create new issues for the future of the clean energy transition? Is WtE investment today logical if the ideal is a clean energy future? Are zero-waste and a circular economy attainable? How else can the problem of waste and landfills be addressed? Are transitional solutions proper climate change solutions that governments should consider? Many questions and concerns surround the WtE debate. Like many other ‘regrets’ solutions, this will shape the evolution of green economies. The debate over how the energy transition should look has no ‘right’ solution; however, the actions taken will define what is considered ‘green’ and ‘sustainable’ by our societies.