By Henry Fowler

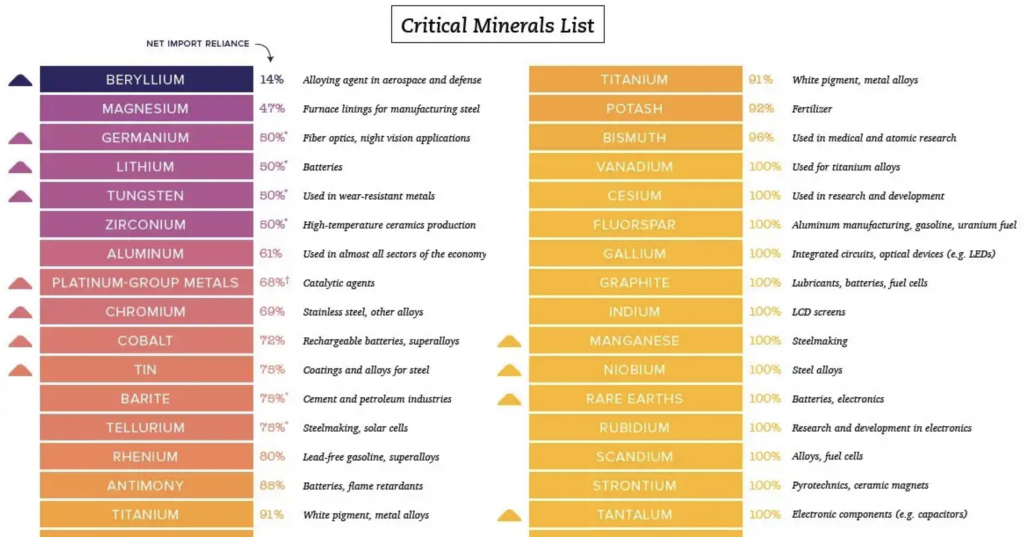

Critical minerals are non-fuel, or mineral materials essential to economic or national security and have a supply chain vulnerable to disruption. The list varies by country, but in Canada, it comprises 31 minerals, most notably aluminum, cobalt, copper, nickel, lithium, and rare earth metals (REMs). Critical minerals are vital components in developing renewable energies and clean energy technology. 2030–35 emission reduction goals, 2050 net zero emission goals, limiting global warming to well below 2ºC (preferably to 1.5ºC) compared to pre-industrial levels, and the greater global energy transition is wholly reliant on the excavation, refinement, implementation, and utilization of these minerals.

In each of the IEA’s energy transition consumption scenarios (States Policies Scenario [STEPS], Sustainable Development Scenario [SDS], and Net Zero Emissions 2050 [NZE50]), the consumption of critical minerals must scale up by a tremendous amount. For example, lithium demand is projected to grow 4200% by 2040 (from 2020 levels), graphite by 2500%, cobalt by 2100%, nickel by 1900%, and REMs by 700%. Further, total mineral demand is expected to quadruple by 2040 (from 2020 levels) to meet the Paris Agreement on climate change (IEA) requirements. Leading the growing demand is the production of electric vehicles (EVs), which batteries demand significant amounts of lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel, and graphite. Offshore/onshore wind farms and solar PV tech closely follow in demand.

The story on critical minerals does not end there. Canada and the rest of the world face several barriers to reaching these supply and demand levels. Before getting into specific threats, supply-side problems are the first problem, with required demand surpassing the projected supply for several minerals. For example, in the absence of further mine development, the lithium market deficit is projected to reach 700Kt by 2030, while the copper market is expected to be in a nearly 4.7Mt deficit by 2030, based on current projections of supply (EY). Current mineral supply and investment plans fall short of what’s needed to transform the energy sector, raising the risk of delayed and more expensive energy transitions. Mining issues around First Nation’s support, community involvement, slow and inefficient explorations, lack of low-carbon energy use on mine sites, lack of leadership from junior mining companies, long and delayed permitting/regulatory processes, the lack of mineral mid-stage refinement in Canada (and subsequent reliance on Asia for this), and the overall dependence on China, Russia, and other geopolitically tense countries for mineral supply are other concerning issues.

Canada has the opportunity to take a leading role in the critical mineral space moving forward. Further, European reliance on Russia’s oil and gas sets Canada up to be able to supply renewable energy amidst the ban on Russian O&G imports. Canada has already taken significant strides by allocating $3.8 billion of the 2022 federal budget to implement Canada’s first Critical Minerals Strategy (Torys). Other solutions needed to be addressed by the (IEA) are; further private-public sector collaboration and investment, increased transparency of mining regulatory processes, early and often community involvement (to further drive jobs, GDP, and exploration), implementation of low-carbon energy on-site (via green/blue hydrogen, CCS, wind, solar, SMRs, etc.), tech R&D along the entire value chain, increased recycling, enhanced supply chain resilience and market transparency, push ESG awareness/standards, and strengthen international collaboration between producers and consumers. Canada is well-positioned to drive critical mineral mining and lead the energy transition. The question is whether they will seize the opportunity first or fall behind another global power.