By ESG McGill Analyst Max Bendjaballah

Quebecers have expressed their desire to see policymakers transform the province into a greener economy. Climate advocates and many academics in the province want to follow Amsterdam’s lead in prioritizing well-being in the decision-making process. While the concept of green growth sounds appealing, many scientists have proven it unworkable and contradictory. Economic growth depends on finite natural resources, making combining environmental limits and increasing production impossible. Thus, the green growth that most parties advocate is utopian in its very terms.

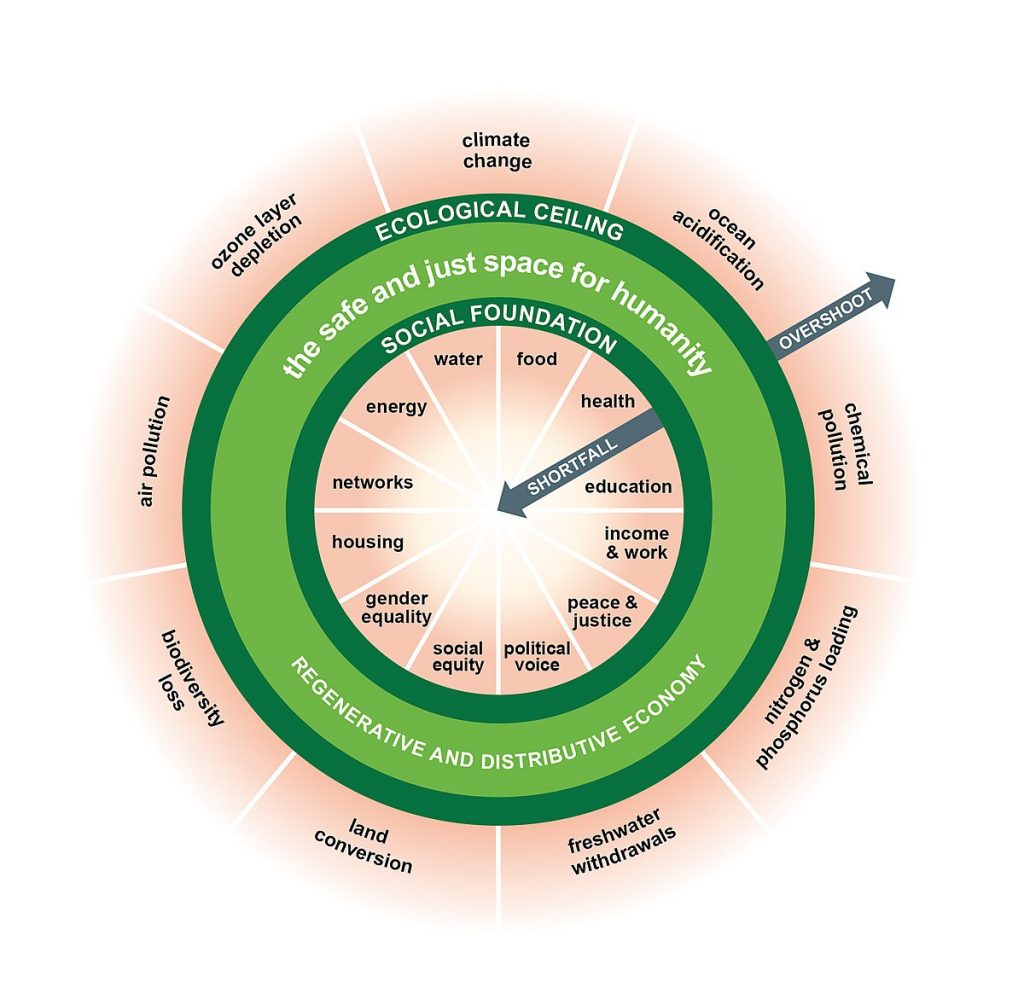

For this reason, alternative models, such as Kate Raworth’s famous representation of the doughnut economy, describe how the 21st-century economy should be understood. The doughnut represents how policymakers can meet the needs of the people (represented in the inner circle) while respecting the ecosystem’s needs (outer circle). This outer boundary is made up of nine vital systems that must be preserved to maintain a stable order. At the same time, the white centre of the doughnut represents the societies that have not yet provided all necessities to their people. The ultimate goal is to reach the green ring called “safe and just space for humanity,” which respects environmental constraints. The concept incorporates the idea of economic degrowth, where the ultimate goal is to reach the green ring and maintain it sustainably circularly using resources. Nevertheless, Raworth insists on the need for developing countries to preserve their economic growth until they reach this sustainable balance.

Amsterdam is the first city to implement a circular economy based on Raworth’s representation. By bringing together a coalition of “changemakers,” the city has committed to simultaneously addressing inequality and climate change issues. Moreover, the application of this model has succeeded in creating a space where diverse individuals can propose innovative solutions for the benefit of the whole population.

To convert Quebec to this mindset, policymakers need data and targets to establish coherent policies and reform the economic system. For almost a century, societies have measured progress using the gross domestic product (GDP) as a unit of account. However, this flawed measure assumes that greater financial opportunity leads to higher well-being while omitting wealth inequality, health and environmental concerns. Simon Kuznets, its creator, warned at its inception that this indicator was inappropriate for measuring well-being. However, policymakers still consider the aggregate unit the most relevant measure.

The G15+ initiative has taken on this mission in Quebec and has created a comprehensive database ranging from environmental to societal indicators to assist decision-makers. In creating “Indicators of Well-Being in Quebec,” the goal is to make welfare the central guideline for policy. The data will show the province’s evolution and progress of key themes. In addition, the group is committed to establishing a high level of cooperation between the federal, provincial and territorial governments.

Their methodology emphasizes the interdependence between the economy, the environment and society. This co-dependence is their guiding principle. The initiative argues that environmental, economic or societal shocks are not exogenous and disproportionately affect specific segments of society. For instance, climate disasters do not have the same impact on the poor and the rich. Nazrul Islam and John Winkel found that climate change and economic inequality lead to a vicious cycle. Existing inequalities make the poorest more vulnerable, and shocks worsen their situation. Subsequently, it also complicates the prospects for recovery. This example shows that reducing inequality requires mitigating climate change, and only considering GDP omits endogenous factors such as the environment.

In summary, the G15+ data allow us to capture the underlying dynamics and effectively address socio-economic issues in Quebec. Policymakers now have better data to put well-being at the centre of their decisions. Now that they have the basis, it is the responsibility of Quebecers to encourage their politicians to look to an alternative economic model.